Your Questions About Natural Gas, Answered

Natural gas is powering our modern way of life and helping to cut CO2 emissions. Here’s what this energy revolution is all about.

Learn MoreNatural gas is powering our modern way of life and helping to cut CO2 emissions. Here’s what this energy revolution is all about.

Learn More

Drew Pomerantz

Principal Research Scientist, Schlumberger-Doll Research Center

Boston, MA

Scientists from across the industry are working on getting the world’s cleanest major fuel source even cleaner. For Drew Pomerantz, that process starts with a Ghostbusters backpack.

Scientists from across the industry are working on getting the world’s cleanest major fuel source even cleaner. For Drew Pomerantz, that process starts with a Ghostbusters backpack.

November 6, 2019

Walking around in the oppressive 100-degree heat of San Antonio, Texas, lugging what he described as a “Ghostbusters” backpack, Drew Pomerantz was a long way from home. It was the summer of 2017, and the principal research scientist at the Schlumberger-Doll Research Center in Boston was in Texas to test a range of cutting-edge technologies helping the industry further reduce greenhouse gas emissions in natural gas production and transportation.

Today, natural gas — the cleanest major fuel source — provides 35% of the power for electricity generation in the United States. The transition to natural gas, replacing other energy sources such as coal, has driven U.S. carbon dioxide emissions to the lowest levels in a generation. Even so, Pomerantz and others in the natural gas and oil industry aren’t satisfied. They see an opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions even further by identifying spots in pipelines where methane, a primary component of natural gas, escapes.

Industry efforts already have helped to significantly reduce methane emissions.

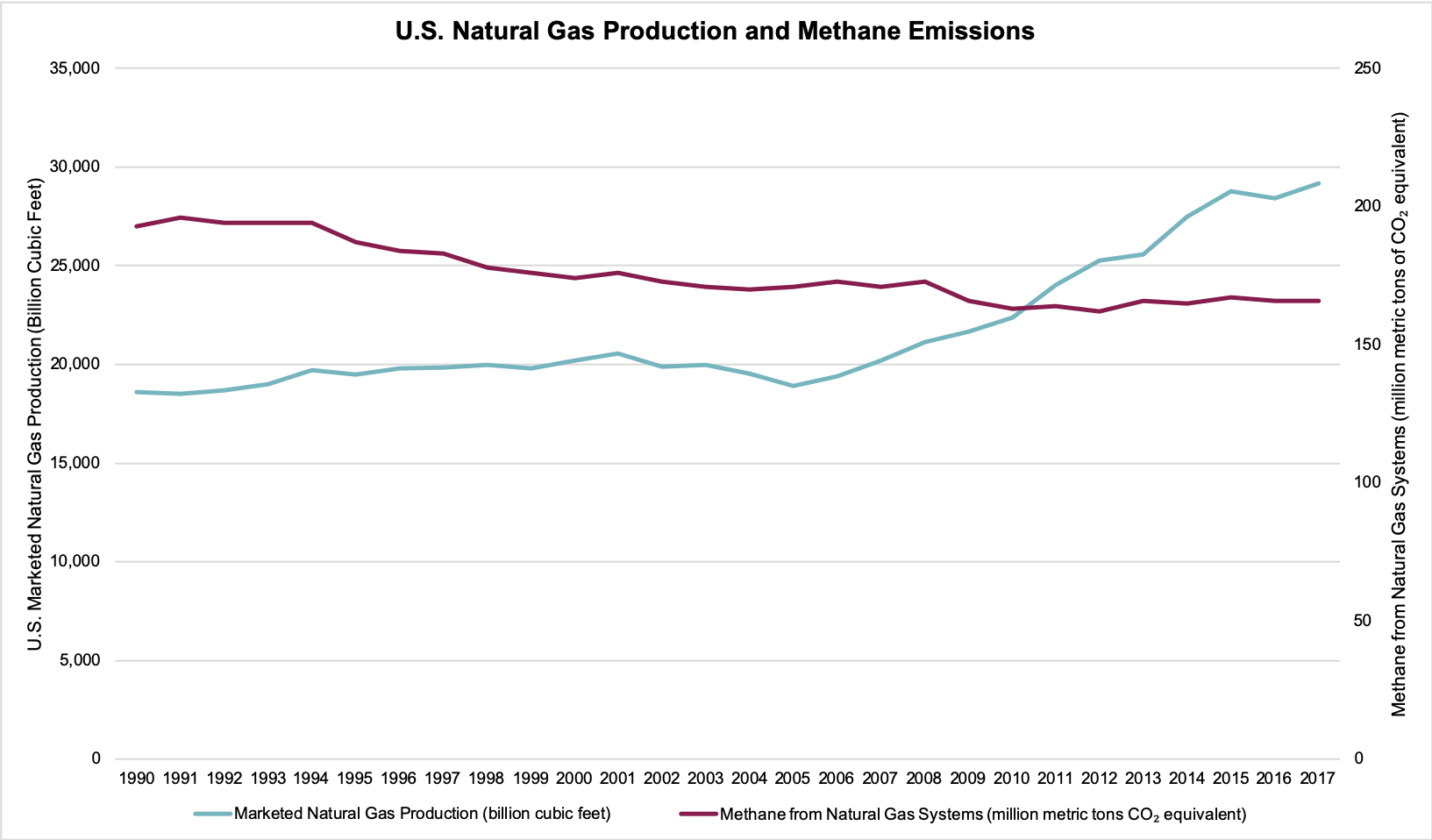

Even as natural gas production increased by more than 70% from 1990 to 2018, the latest EPA Greenhouse Gas Inventory shows an overall decline of 23% in methane emissions from petroleum and natural gas in the same period.

Pomerantz says his research into various technologies and far-reaching partnerships can drive those numbers even lower — and soon.

“For natural gas to fulfill its societal role as a primary fuel source today, and a long-term partner to more intermittent renewable energy, we must reduce the environmental footprint caused by methane leaks,” he says.

It’s this truth that led Pomerantz, his fellow scientists, and partners at the Environmental Defense Fund to the dry plains of Texas. Specialized work crews often travel to remote locations to manually test well sites, but Pomerantz learned that nine out of 10 times crews find nothing needs to be addressed at the site. A better idea, he thought, would be to use automated technologies to pinpoint issues so that crews only travel to sites with a known problem.

As a result, his team spent two years exploring the hundreds of methane detection technologies being produced by entrepreneurs, academics and private corporations. Then they invited the creators of the top 15 technologies out for a field test in San Antonio to see how well they worked.

Two years later, the work continues. His team has evaluated onsite sensors, sensors carried by airplanes and helicopters and the use of satellite technology to aid in detection.

“These sensors under development range from a couple of bucks to millions of dollars and everything in between,” he says. “Exploring all of these technologies is important because there is no one-size-fits-all option.”

Colorado State & Partners Want to See How Low Methane Emissions Can Go

Learn more.To keep exploring the many options for a range of situations, Pomerantz continues to partner with operators, academics, environmentalists and entrepreneurs.

“My job checks all of the boxes to keep me interested as a scientist,” he says. “I am working on compelling research and placing papers in academic journals. At the same time, the research could have an impact within the energy industry and even on the planet.”

More From API

Read on for in-depth articles about how we’re securing America’s energy future, our efforts to combat climate change, and more.

Siemens’ Pratyush Nag and team are ushering in electricity’s future.

Learn MoreCyberattacks threaten our energy infrastructure. See how Marisa Ruffolo and her Chevron colleagues protect an essential industry.

Learn MoreWe use cookies to offer you a better browsing experience, analyze site traffic, personalize content, and serve targeted advertisements. If you continue to use this site, you consent to the use of cookies. Read more about our Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions.

accept